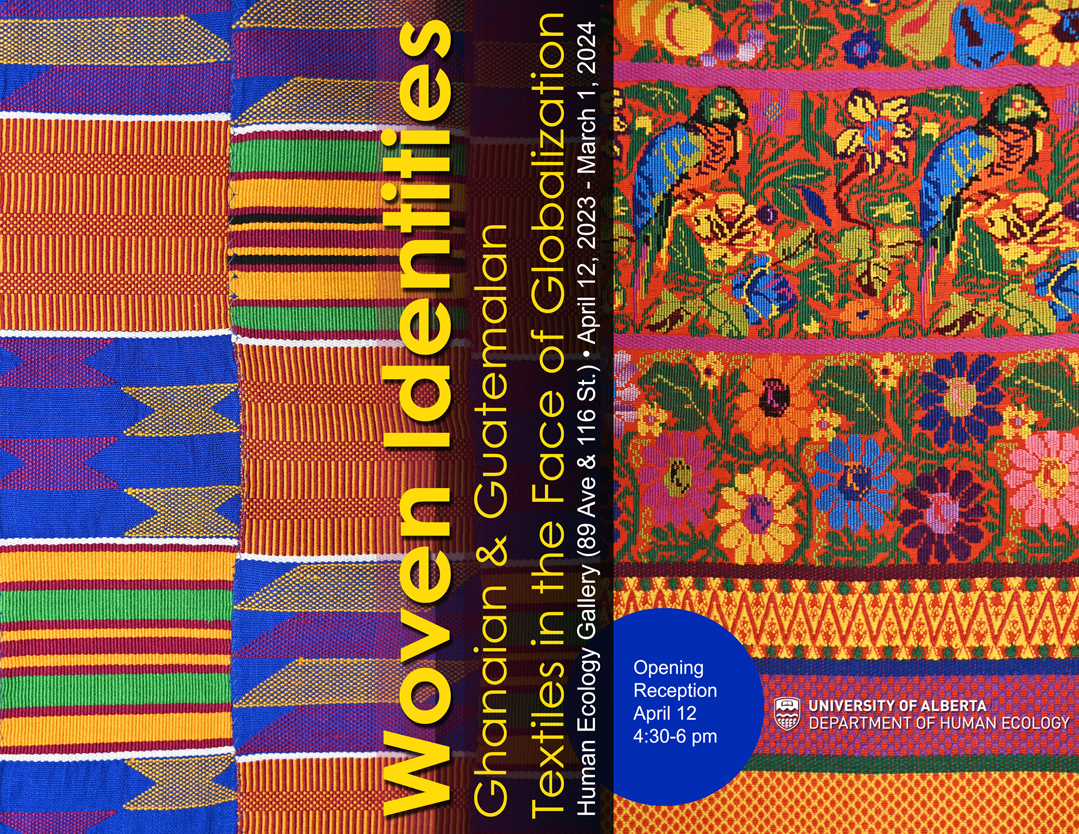

April 12, 2023 - March 1, 2024

Curators

Anne Bissonnette, PhD, Siming Guo, PhD, Elsie Osei, MFA, and Chiara Power, BA

Woven Identities:

Ghanaian and Guatemalan Textiles in the Face of Globalization

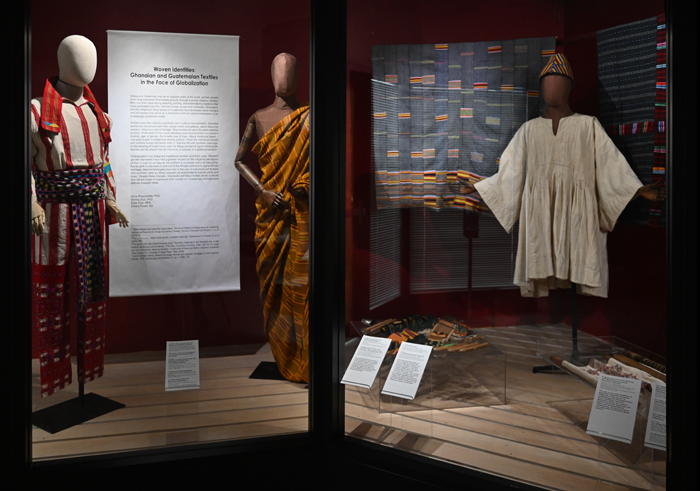

Ghana and Guatemala may be on opposite sides of the world, yet their people have long expressed themselves proudly through a similar medium: textiles. Both countries have strong weaving, printing, and embroidering traditions that have generated colourful, intricate textiles recognized worldwide. Ghanaians and the indigenous Maya people of Guatemala have developed woven designs and processes that serve as a distinctive form of cultural expression in an increasingly globalized world.

Textiles have often played a significant role in cultural representation. Ghanaian textiles are remarkable with their unique motifs and patterns, which reflect the country’s indigenous cultural heritage.[1] Maya textiles can serve the same collective purpose. While some of their visual elements could once be linked to a wearer’s location, age, or gender, the broader use of traje—Maya traditional dress—now plays a part in indigenous identity politics.[2] From the individual colours and symbols woven into kente cloth that are rife with symbolic meanings, to the wearing of huipil tunics worn by Maya woman to signal ethnic pride, textiles can be viewed from an individual, a national, or a global perspective.[3]

Globalization has impacted traditional textiles and their uses. Western gender standards have had a greater impact on the negative perception of men in traje as they do not conform to a somber vision of masculinity. Kente cloth is now worn in and out of the African continent to signal African heritage. New technologies have led to the use of manufactured threads and synthetic dyes by Maya weavers as substitutes to natural yarns and dyes.[4]

Despite these changes, Ghanaians and Maya textiles remain a valued and vibrant mode of expression that counter an increasingly homogenized attitude towards dress.

Anne Bissonnette, PhD

Siming Guo, PhD

Elsie Osei, MFA

Chiara Power, BA

[1] William Badoe and Nana Afia Opoku-Asare, “Structural Patterns in Asante Kente: An Indigenous Instructional Resource for Design Education in Textiles,” Journal of Education and Practice 5, no. 25 (2014): 52.

[2] Morna MacLeod, “Mayan dress as text: contested meanings,” Development in Practice 14, no. 5 (2004): 683.

[3] For kente cloth, see Robert Kingsley Ayiku, “Symbolic meanings in the Ghanaian arts: a step towards developing cultural literacy” (PhD diss., Concordia University, 1998), 150-159. For huipil, see Carol Hendrikson, Weaving Identities: Construction of Dress and Self in a Highland Guatemala Town (Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 1995), 63-64.

[4] Janet Catherine Berlo, “Beyond Bricolage: Women and Aesthetic Strategies in Latin American Textiles,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics 22, no. 1 (1992): 123.