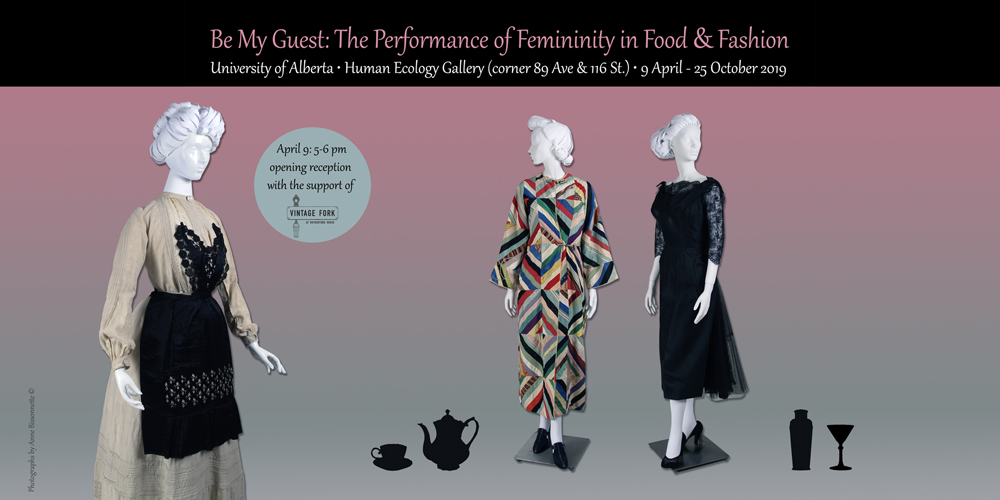

9 April to 25 October 2019

Curators

Carolina Amaral, Anne Bissonnette, PhD, Elizabeth Brandeau, Leah Hrycun, Katelin Karbonik and Amber Peters, exhibition co-curators

Be My Guest:

The Performance of Femininity

through Food & Fashion

Unspoken social rules are part of our lives. Instructions given by etiquette writers have deep roots that still affect how we dress and behave in social gatherings. By the late 19th century, many women carved out domestic spaces as their own. As a hostess, a woman could find ways to assert her power in the domestic sphere and further her family’s standing through a variety of receptions. Home could be both a private refuge and a public place to entertain an array of guests with food and festivities. From the Victorian front parlour tea, to the modernist living room cocktail party, to formal and informal dining room events, women have negotiated their roles as hostesses and guests in numerous ways. This exhibition explores the performance of femininity through dress and the objects of home entertaining that broaden one’s social network.

Feminized domestic roles endure. Advertising has been effective in cementing constructs that intertwine women with notions of food preparation and love.[1] While men’s participation in food preparation in the home is increasing, this form of (undervalued) labour continues to be performed overwhelmingly by women.[2] When opening one’s home to others, the same social anxiety Victorian women felt may still be with us today. Contradictory messages aimed at hostesses continue to suggest the use of certain products as a guarantee for success, while catering to women’s desire to be modern and progressive, thus conflating traditional and egalitarian ideas in one seductive package.[3] These tensions have resulted in a variety of gatherings. The kinds of food we prepare, the manner in which we share this food (2), and the types of garments developed around these occasions have evolved. The changing etiquette for these events speaks of changing mores.

Transformations in domestic architecture echo the growing informality of our lives. Victorian rules of conduct were quite complex. Dress categories for women included undress (garments worn inside the home), half dress (clothing fit to be worn outside the home), and full dress (attire worn at ceremonial and evening events). Each had levels of formality that are echoed in our current lives. What should a woman wear when invited to the home of a supervisor, her in-laws, or a co-worker? While men can typically get away with a daytime suit, a woman can find herself overdressed or underdressed, which may have social consequences. When a hostess can be seen cooking and serving in her modern home, she may wish for a polished apron (1) to protect her clothes and, in so doing, perpetuate domestic stereotypes.

Carolina Amaral

Anne Bissonnette, PhD

Elizabeth Brandeau

Leah Hrycun

Katelin Karbonik

Amber Peters

[1] Katherine Parkin, “Campbell’s Soup and the Long Shelf Life of Traditional Gender Roles,” in Kitchen Culture in America: Popular Representations of Food, Gender, and Race, ed. Sherrie A. Inness (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001), 51-53.

[2] In 2016, an average of 70% of females and 46% of males cooked in US homes. See Table 1 in Lindsey Smith Taillie, “Who’s cooking? Trends in US home food preparation by gender, education, and race/ethnicity from 2003 to 2016,” Nutrition Journal 17, no. 1 (2018): 41.

[3] Elizabeth A. Sharp, “Betty Crocker Versus Betty Friedan: Meanings of Wifehood Within a Postfeminist Era,” Journal of Family Issues 39, no. 4 (December 2018): 845.