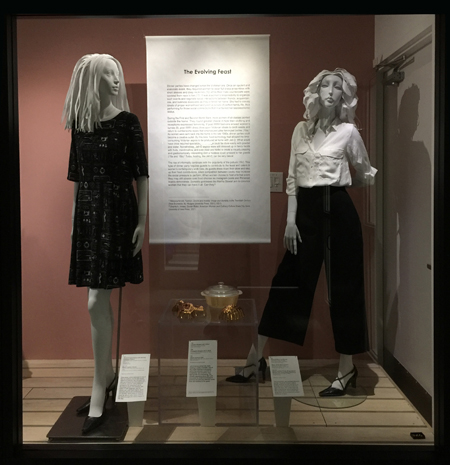

Dinner parties have changed since the Victorian era. Once an opulent and elaborate event, they required women to wear full dress ensembles with short sleeves and deep necklines (12) while their male counterparts were covered from neck to toe (13). It was a woman’s responsibility to organize such events and negotiate social interactions between friends, acquaintances, and business associates as they entered her home. She had to convey ideals of proper womanhood and paint a picture of perfect family life, thus performing for those social connections that maintained her socioeconomic status.

During the First and Second World Wars, more women of all classes worked outside the home. They found greater choice in how their clothing and receptions expressed femininity. If post-WWI fashions erased women’s curves (9), post-WWII dress drew upon Victorian ideals to cinch waists and return to cumbersome styles that emphasized ultra-feminized bodies (10a).[1] As women were sent back into the home in the late 1940s, dinner parties could become a creative outlet. By this time, food technology had allowed the time-consuming Victorian aspics to be produced at home with Jell-O. What would have once required specialized knowledge could be done easily with powder and water. Nonetheless, Jell-O aspics were still dressed up in fancy molds with fruits, marshmallow, and even meat and herbs to create a visually pleasing and gastronomically interesting dish a hostess could present to her guests (15a and 15b).[2] Today, hosting, like Jell-O, can be very casual.

The rise of informality continues with the popularity of the potluck (15c). This type of dinner party requires guests to contribute to the feast and caters to women’s contemporary work lives. As guests dress down their attire and step up their food contributions, silent competition between cooks may increase the social pressure to perform. When women choose to host a formal event, they may still obsess over food choices as Instagram posts and Pinterest boards demonstrate. Domestic goddesses like Martha Stewart aim to convince women that they can have it all. Can they?

[1] Rebecca Arnold, Fashion, Desire and Anxiety: Image and Mortality in the Twentieth Century (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2001), 102-3.

[2] Sherrie A. Inness, Dinner Roles: American Women and Culinary Culture (Iowa City, Iowa: University of Iowa Press, 2001).

Be My Guest: The Performance of Femininity through Food & Fashion

9 April to 25 October 2019

Carolina Amaral, Anne Bissonnette, PhD, Elizabeth Brandeau, Leah Hrycun, Katelin Karbonik and Amber Peters, exhibition co-curators