DRESS & ESCAPISM - THE DRESS RESEARCH EXHIBITION SERIES

Part 1 of 3: Dress Artifacts & Curatorial Practices

A Virtual (and Evolving) Exhibition

Anne Bissonnette, Lead Curator

Josée Chartrand and Katelin Karbonik, Contributing Curators

June 30, 2020 – June 30, 2021

Part 1 Home | The Blair Suit Reproduction | The Robe à la Française Reproduction | The Mid-1790s Chintz Gown | The Chemise Dress | The 1796 Reproduction Wedding Gown | The Housemaid's Dress

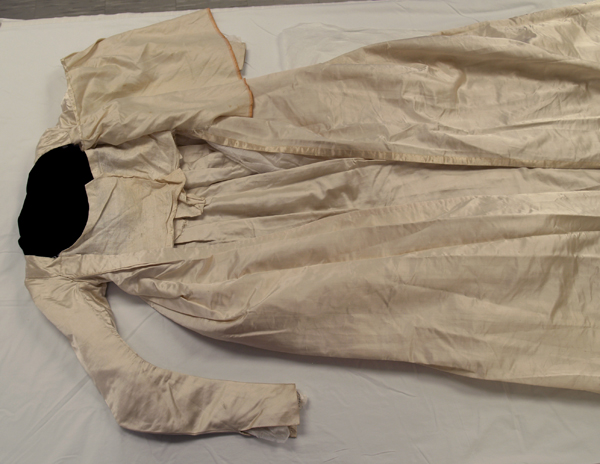

Open robe and petticoat

Made by Sarah Woodyard, 2019

Acetate, cotton or linen lining

On loan courtesy of Sarah Woodyard

Mount, photographs, and montage by Anne Bissonnette©

Very few garments survive with the complete story of who made, wore and kept the garment, under what circumstances it was made, sold, worn and possibly altered, and where. This story of ownership called “provenance” is often “used as a guide to authenticity or quality" of a work of art or an antique.[1] Dress artifacts with provenance are often ceremonial, sentimental garments, such as wedding dresses. In these cases, a precise date of production can often be assumed. Nonetheless, a gown worn for a wedding may still have been altered for a new user and worn after its initial use. Additionally, the memory of the keepers of such pieces and the information transferred from one person to another may be faulty. As a result, researchers are always pleased to find artifacts with provenance but they still observe them and their stories with a critical eye. This is the case for a 1796 wedding ensemble from the Costume Collections of the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Art Museums at Colonial Williamsburg. According to museum records, the gown is said to have been worn by Mary Willis, who was born in Massachusetts on December 13, 1774.[2] Those records also indicate that she married Peter Osgood (1764-1856) on July 13, 1796, and died on October 23, 1825. In addition, we also know that the artifacts descended through her child Abigail Bailey Osgood (born 1798).

The wedding ensemble is composed of an ivory silk open robe with a series of short pleats at the upper back section and a petticoat of the same fabric. The petticoat shows evidence of alterations: there are large tucks on its narrow linen waistband. As few skirts from ensembles from that period have survived, we cannot know how the petticoat may have originally looked, despite the evidence of alteration. Was the petticoat re-constructed or was it simply made smaller at the waist for another user? We don’t know.

When faced with the task of mounting this ensemble on a mannequin, several questions come up. Some questions may emerge from the close examination of the artifact. Can the structure of the petticoat help us understand how it was placed on the body? This may be the case for this petticoat as unstitched portions of panels at the right side near the waistband could be used as a pocket slit. If so, this could place an inverted pleat at the centre front and the opening of the waistband at centre back. While we assume that waistbands must lie at the waist level, pinning the linen waistband to the boned stays to create an elevated waistline may be a possibility that would echo the elevated waistline of the open robe. However, if the petticoat was re-used many generations later, it may have been tucked-in at the waistband to create a smaller size that was no longer pinned higher up and thus fell to the natural waist. We cannot know for sure that the ensemble, as it currently stands, is truly as it was in 1796.

Many questions about late 18th century dress practices arise when we observe and mount this ensemble. How did women bring their outer most (visible) petticoat up above the natural level as waistlines rose ? If they pinned them to stays, this could help to explain why traditional, boned, conical stays remained in use despite rising waistlines that did not emphasize a small waist. Stays provided a solid anchor point for women to pin various parts of their garments into, and had been used in this way for many years. The wearing of stays was, by the late 18th century, a centuries-old practice, and thus less easily changed than more superficial fashion trends. Other means to raise petticoats could also exist, such as the use of removable or sewn-in suspenders.[3] Tape pinned to the front neckline of stays, crossing at centre back, and reaching to the front waist could also serve to secure a petticoat higher than the natural waist (Figures 1 and 2). This would help when stays begin to lose their all-over boning (becoming more difficult to pin into) and prevent straps from falling over the shoulders. Some shorter transitional stays also have added small cushions to prohibit the fall of the petticoat, which could also be done with padded and stiffened tabs, but this would not work when the lining of the gown reaches to the natural waist, as is the case for our artifact.[4] We may not have ready answers by looking at artifacts alone, but we can investigate clues embedded in their construction.

Figure 1

Stays

1785-1790, 18th century

39.8 cm

Gift of Mrs. Hamilton

M969X.26

© McCord Museum

Link to the museum artifact

Figure 2

Stays

1785-1790, 18th century

39.8 cm

Gift of Mrs. Hamilton

M969X.26

© McCord Museum

Link to the museum artifact

The "open robe" (a type of garment opened at centre front from neck to hem) of the wedding ensemble, like the petticoat, may have been altered. The linen lining at the bodice has two panels that form a triangular back section that measures 29 cm, a length that could reach below the natural waist (Figure 3). This is much longer than where the most central back pleats end at 11.8 cm, which generates the elevated waistline. Still, it is possible that mantua-makers (i.e. dressmakers) continued to make garments following the same formula they knew. This could consist of draping, cutting, and fitting the lining directly over the client dressed in her stays, and then manipulating and attaching the fashion fabric, cut as little as possible, over the lining.[5] If long traditional stays were worn, then it may be that the lining followed the length of the stays, despite the fashion fabric being manipulated to create an elevated waistline. Unlike the mid-1790s chintz gown explored earlier, there is no fashion fabric cut to conform to the shape of the long lining, a feature that heavily suggests that the chintz gown was remade from an earlier style that defined the natural waistline. However, this does not mean that the wedding gown escaped alteration. It is possible that mantua-makers could have unstitched the fashion fabric of the wedding gown and re-draped it according to new trends. Creating a pattern of the ensemble and exploring this possibility could help to find answers to this and other questions that arise when transitional 1790s dress is studied and often leave the researchers puzzled. There may be a simple answer rooted in the production process.

Figure 3

Bodice lining detail of a gown and petticoat ensemble

Worn in Massachusetts, Textile produced in China, 1796

Silk, linen lining

Gift of Tibo van der Does

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (2007-104, 1-2)

Research photograph by Anne Bissonnette©, used with permission from The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Sarah Woodyard, a master mantua-maker and milliner trained at Colonial Williamsburg and a graduate of the University of Alberta’s Masters Program in Material Culture, reproduced the 1796 wedding ensemble with great precision. Like her former supervisor, Dr. Bissonnette, she was puzzled by a loose panel stitched to the left of the gown’s neckline over the linen lining front sections (Figure 4). The loose panel is nearly twice as long as the left and right front linen lining (Figure 5). The hand (i.e. drapability) and shine of the loose panel of silk fabric are different from the rest of the fashion fabric used on the open robe and petticoat. This points to the fact that the loose panel is made of a different fabric than the rest of the ensemble. Was this loose panel added later to cover the torso when the petticoat was tucked and worn at the natural waist? Without the loose panel, what covered the lining in front? If triangular stomachers were pinned in that area earlier in the 18th century, they were no longer in fashion at the end of the century. We can wonder if such loose panels were then used instead. If so, the loose panel had to be tucked in the petticoat to hide the hem, which is cut along a selvage and features yellow threads. To help explain this gown and the transition away from earlier open robes worn with stomachers, other artifacts were consulted to help mount the reproduction ensemble.

Figure 4

Bodice detail of a gown and petticoat ensemble

Worn in Massachusetts, Textile produced in China, 1796

Silk, linen lining

Gift of Tibo van der Does

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (2007-104, 1-2)

Research photograph by Anne Bissonnette©, used with permission from The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Figure 5

Bodice detail of a gown and petticoat ensemble

Worn in Massachusetts, Textile produced in China, 1796

Silk, linen lining

Gift of Tibo van der Does

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (2007-104, 1-2)

Research photograph by Anne Bissonnette©, used with permission from The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

A turquoise silk ensemble from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco is most informative. It has a similar cut to our wedding ensemble, as both consist of an open robe with a series of short pleats at the upper back section and a petticoat of the same fabric. The petticoat may have been altered. It currently has a wide silk-covered waistband that sits at the natural waistline. We know the waistband-skirt seam rests at the natural waist level because the hem of the open robe falls slightly below the hem of the petticoat, as is customary in the 18th century. The petticoat’s waistband is fairly wide, covering the lower part of the bodice front panels. The linen bodice panels reach the natural waist and the turquoise silk fabric is stitched over the linen but for the lower portion where the wide waistband lies. The maker likely knew the wide waistband would cover this area. Based on this artifact, we can suggest that an elevated waistline on an open robe may not be mutually incompatible to a petticoat worn at the natural waist, providing no alternations of the ensemble were made. The lining has the inscription “April 30 1789.” This is seven years before our 1796 wedding ensemble, at a time when dress behaviors were changing considerably. Is the wearer of the turquoise ensemble an early adopter and the wearer of the 1796 ensemble conservative in her approach? What about the loose panel in the 1796 robe? Could it have been added to modify the garment? This is where we can turn to fashion plates for further clues of this period on transition.

Fashion plates around the years 1789 and 1796 can provide unique information: they can convey silhouettes, accessories, and a variety of styles and dress behaviours. Such plates may describe novelty styles but these may not be adopted quickly, enthusiastically or at all. Did the turquoise ensemble emerge in its current form on the eve of the French Revolution and remain fashionable for many years? Both gowns come with a date that can help us better understand this situation.

On April 11, 1789, The Magasin des Modes Nouvelles Françaises et Anglaises (quatrième année, no. 14) published Planche II, where a woman can be seen in a hunter green open robe with a white, relatively narrow petticoat. The bodice of the green open robe is visible because, unlike many of her contemporaries with large kerchiefs covering their bodices, she wears a white “fichu-chemise” (i.e. kerchief that looks like a shift) tucked into her gown.[6] As the petticoat is made of linon (i.e. a fine and sheer linen or cotton fabric) and the “fichu-chemise” is made of gaze (i.e. a fine and sheer cotton or silk fabric), we know these are separate items.[7] The front section of her open robe is flat. We cannot see the back bodice but the skirt drapes to form a train in back, exposing the petticoat at the front and reaching to where the side seams would be. A wide pink sash is worn that starts at the natural waist level and is similar in width to the turquoise petticoat from the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. The sash covers the gown in back, is tied with a large bow to the side, and ends nearly to the floor. This fashion plate makes it plausible that the turquoise ensemble was worn in April 1789 even if this is not the only style depicted at this time.

Many gowns from 1789 have long fitted sleeves, wide sashes, and relatively narrow skirts in comparison to garments seen earlier in the decade. The torso remains conical overall, which suggests the continued use of traditional stays in 1789. The pointed front bodices popular throughout the 18th century can still be seen, often below the waist sash, belt, or ribbon, but their absence is frequent too. The same is true for back bodices: some are pointed in back, as they had been for a long time, while others have done away with this traditional feature. While the April 30, 1789, date inscribed on the turquoise robe’s lining is plausible, the short back pleats producing an elevated waistline on the open robe remain undocumented in other 1789 primary sources. Does the placement of a wide sash over the open robe and petticoat create the fashionable longer torso of 1789? Mounting the gown with a wide sash could help us get an answer. Maybe the back of the turquoise open robe was modified later? Such questions remain unanswered but the use of a sash over the turquoise open robe is likely and could also apply to our 1796 reproduction robe. To find out if such an ensemble remains fashionable in 1796, we can search for examples in fashion plates from this period as well.

A survey of all fashion plates depicting women in the 1796 Gallery of Fashion can help us assess how fashionable the 1796 reproduced elevated waist, long-sleeved, open robe would be in England. Of the 36 figures where the waist level can be seen, 32 are elevated (88.9%), which would make that feature of the wedding ensemble quite fashionable. However, of the 43 figures where we can assess the gown style, only 9 wear open gowns (20.9%) while 24 wear round gowns (55.8%). Open robes are thus less popular, as is also the case for long sleeves: of the 40 female figures with visible sleeves, 3 wear long sleeves (7.5%) while elbow-length sleeves are worn by 35 (87.5%). Short pleats at the back of a gown were found in a German fashion plate from the 1797 Journal des Luxus und der Moden. By 1797, when French fashion plates return through the Journal des Dames et des Modes, the waist level typically rests bellow the bust but elevated waistlines that are not placed directly below the bust are still present and represent 33% of figures.[8] Most cinching at the waist is done with a narrow ribbon or sash but wider waist sashes are still occasionally seen in 1797. This may serve to explain the narrower linen waistband of the 1796 silk petticoat. A study of all plates accessed from the Journal des Dames et des Modes between 20 March to 31 December 1797 concluded that long sleeves that end at the wrist or bellow are depicted in 12 of 14 women’s garments (86%) but that, in the next two years, their popularity fell to 44%.[9] By 1797, we are at the cusp of change but, until the end of the 18th century, “various fullness of skirts, sleeve lengths, colours and waist levels are numerous and coexist.”[10] Where the gown was worn and if a person followed English or French fashion could affect the fashionability of our 1796 wedding ensemble.

With this data in hand, we can try to better understand our 1796 wedding ensemble. Its long fitted sleeves remain somewhat fashionable in England in 1796 (likely more so in France) but are a stylistic feature that has been seen for a while and will soon wane in popularity. The short pleated back may be novel, as the 1797 German plate’s illustrator made it a point to depict this feature. Such short pleats may have been done earlier, as in the case of the turquoise robe, if we assume that it was not altered later on. Like this turquoise robe, our 1796 wedding open robe has flat front panels that fit well over traditional conical stays, which are echoed in its long back lining panels. The back lining and the shape of the front lining panels are similar to those of the turquoise robe (albeit covered in fashion fabric in the case of the front panels). This suggests the possibility that the 1796 robe may have been altered from an earlier style. However, this traditional approach to dress construction may have lingered. With the economy of cut traditionally practiced by mantua-makers, the short pleated back style may be a new manipulation of the cloth that remained feasible from an earlier style. This is where future research on transitional styles could go. The loose silk front panel is much clumsier in execution and its different fabric make it likely that it was added later. On the other hand, if can be used to create a looser chemise front style that gets tucked under the sash. This can be seen in a figure (far right) from an engraving entitled “Ladies in the Dresses of the Year 1792” (Figure 6), likely from The Ladies' Own Memorandum Book. This style also lingers and can be seen in a French fashion plate (#3) from the 1798 Journal des Dames et des Modes. The loose panel could also be added generations later when the petticoat’s waistline was tucked in and worn at the natural waist.

Figure 6

Excised engraving entitled “Ladies in the Dresses of the Year 1792”

Courtesy of the Fashion Museum, Bath & North East Somerset Council (BATMC 2008.10.27)

Photograph by Anne Bissonnette©

Provenance is helpful but often leaves out or even obscures the full story of a garment. Looking at any garment―with provenance or without―we cannot assume it was the most novel fashion or if it was worn in novel ways. A close examination of the 1796 wedding ensemble leads to several findings embedded in its construction. The evidence indicates the possible presence of tie-in pockets because of a pocket slip on the right side. A fair amount of volume at the skirt might thus be indicated so that bulky items in the pocket do not disturb a linear silhouette. The long lining at the bodice suggests traditional conical stays continued to be worn, which may be a more conservative dress behavior at this time. A survey of fashion plates from the 1796 Gallery of Fashion and the 1797 Journal des Dames et des Modes suggests the predominance of a new aesthetic for the upper body. By then, we witness a change to the “natural” body seen in ancient statuary, where breasts appear as separate volumes. Gowns shown in profile also curve under the breasts rather than fall in a straight line, as would be the case with the wearing of traditional stays.[11] Observing other gowns known to be worn in different countries or cities could map changes in embodiment. With knowledge of the popularity of higher waistlines and the knowledge that lower waistlines were also worn in France in 1797, can we dress the 1796 ensemble with certainty?

Most visitors to an exhibition will view a mounted garment and assume it is accurately presented, yet it is clear that mounting is a subjective enterprise, even when extensive research is conducted. Should a person mount the 1796 ensemble with the skirt at the natural waist and a wide sash over the exposed loose panel but under the back portion of the robe (Figure 7)? Would it be best to pin the petticoat’s waistband higher and then either tuck the neckerchief in at the neckline or drape it over the loose panel (Figure 8)? This later option would have the advantage of hiding the poor craftsmanship of this component in the original artifact. Should the sash cover the robe (Figure 9)? Even with the skirt slightly above the natural waistline, the placing of a bow in back accommodates the shorter pleats of the robe. Or should the narrow linen waistband of the silk petticoat, the short back pleats of the gown, and the documented presence of an attached narrow belt on a similar back pleated garment (Figure 10) lead to the superimposition of the petticoat over the linen lining, its pinning much higher to the stays and the use of a narrow ribbon over the ensemble? The “truth” (i.e. how the gown was actually worn in the past) could lie somewhere in between these options.

Figures 7, 8, 9

The 1796 reproduction wedding ensemble

Made by Sarah Woodyard, 2019

Acetate, cotton or linen lining

On loan courtesy of Sarah Woodyard

Copy of an ensemble in the collection of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation (2007.104.1ab)

Mount, photographs, and montage by Anne Bissonnette©

Figure 10

White cotton open robe and attached belt of the same fabric

Unknown creator and place of origins, 1790s

Cotton embroidered with floral sprigs

Kent State University Museum

Purchase (2006.25.1)

Photographs and montage by Anne Bissonnette, courtesy of the Kent State University Museum

Link to the museum artifact

Have you come across dress artifacts with provenance that leave you perplexed?

Share your thoughts by e-mailing anne.bissonnette@ualberta.ca and we may add your story to bring different perspectives on this subject.

[1] Oxford English Dictionary Online, s.v. “Provenance,” https://www.oed.com/view/Entry/153408?redirectedFrom=provenance#eid.

[2] E-mail communication with Neil Hurst, Associate Curator of Costume and Textiles at The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, July 13, 2020.

[3] A ca. 1810 white spotted fine cotton bodice and skirt from the Warwick Museums (accession number 1962/95/E) appears to have ribbons attached to a waistband of different fabric on the skirt that may document a suspender system that could be used earlier too. Emily Joan Taylor, "Women's dresses from eighteenth-century Scotland: fashion objects and identities" (PhD diss., University of Glasgow, 2013), 51, http://theses.gla.ac.uk/4772/.

[4] “Stays,” T.237-1983, V&A Website, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O138889/stays-unknown/.

[5] For more on the economy of cut present in “all-over pleated” bodices and draping on the client, see David E.Lazaro and Patricia Campbell Warner, "All-Over Pleated Bodice: Dressmaking in Transition, 1780–1805," Dress 31, no. 1 (2004): 16, 19, 20.

[6] “Hand coloured engraving,” 2002.139/829, Museum of London Website, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/732795.html.

[7] For linon, see Larousee online, s.v. “linon,” https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/linon/47291?q=linon#47221. For gaze, see Larousee online, s.v. “gaze,” https://www.larousse.fr/dictionnaires/francais/gaze/36360#definition. For knowledge of fabric use on plate, see “Hand coloured engraving,” 2002.139/829, Museum of London Website, https://collections.museumoflondon.org.uk/online/object/732795.html.

[8] Anne Bissonnette, “Dessiné d'après nature: Renditions from Life in the Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1798‐9," Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 38, no. 2 (2015): 228, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1754-0208.12205.

[9] Anne Bissonnette, “Dessiné d'après nature: Renditions from Life in the Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1798‐9," Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 38, no. 2 (2015): 228, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1754-0208.12205.

[10] Anne Bissonnette, “Dessiné d'après nature: Renditions from Life in the Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1798‐9," Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 38, no. 2 (2015): 215, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1754-0208.12205.

[11] Anne Bissonnette, “Dessiné d'après nature: Renditions from Life in the Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1798‐9," Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 38, no. 2 (2015): 227, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1754-0208.12205.

Support for the exhibition was provided by a KIAS Dialogue Grant from the Kule Institute for Advanced Study and a CIP Artist Project Grant by the Edmonton Arts Council and the City of Edmonton.

This exhibition draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The following individuals have contributed to Dr. Bissonnette’s research thus far: Josée Chartrand, Meg Furler, Peggy Isley, Katelin Karbonik, Patricia Siferd, and Sarah Woodyard.