DRESS & ESCAPISM - THE DRESS RESEARCH EXHIBITION SERIES

Part 1 of 3: Dress Artifacts & Curatorial Practices

A Virtual (and Evolving) Exhibition

Anne Bissonnette, Lead Curator

Josée Chartrand and Katelin Karbonik, Contributing Curators

June 30, 2020 – June 30, 2021

Part 1 Home | The Blair Suit Reproduction | The Robe à la Française Reproduction | The Mid-1790s Chintz Gown | The Chemise Dress | The 1796 Reproduction Wedding Gown | The Housemaid's Dress

Ivory floral open robe with cotton or linen lining, ivory floral bandeau, and light pink petticoat

Unknown creator and place of origin, may be American from English block-printed cotton, first made in the 1780s and altered in the mid-1790s.

Cotton plain weave

Anne Lambert Clothing and Textiles Collection, Department of Human Ecology, University of Alberta

Purchased (2014.1.3 abcd)

Mount and photographs by Anne Bissonnette©

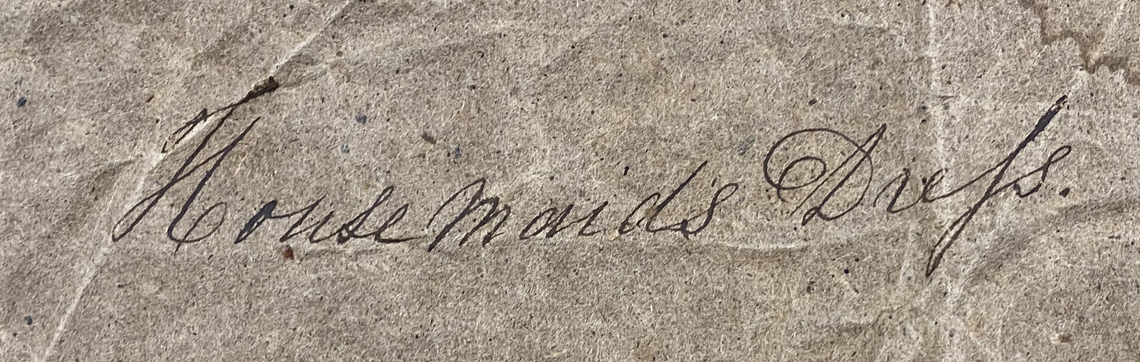

This ensemble came to New York costume and textile dealer Titi Halle of Cora Ginsburg LLC in an old paper bag inscribed with the words “Housemaid’s dreʃs” (Figure 1). It is impossible to substantiate this provenance, but the robe, which was made of a what may have been a very costly textile, as well as the petticoat had some staining that may explain why it could have been given to a housemaid. Once again, the open robe is altered from an earlier style and difficult to document. It still possesses tapes and loops in the robe’s skirt panel to drape the skirt over the petticoat (Figure 2) as was the fashion in the 1780s (Figure 3). The robe can be draped in a similar manner, but we do not know for sure that it was despite the presence of the mechanism, which may have been and earlier mechanism that went unused in a later alteration. We do not know if it was altered significantly to fit the (very small body of the) housemaid and the latest trends. Class, context, and use are seldom documented in museum records.

Figure 1

Detail of the paper bag that contained the ivory floral open robe with cotton or linen lining, ivory floral bandeau, and light pink petticoat

Unknown creator and place of origin, may be American.

Paper

Anne Lambert Clothing and Textiles Collection, Department of Human Ecology, University of Alberta

Purchased (2014.1.3d)

Photographs by Anne Bissonnette©

Figure 2

Ivory floral open robe with cotton or linen lining, ivory floral bandeau, and light pink petticoat

Unknown creator and place of origin, may be American from English block-printed cotton, first made in the 1780s and altered in the mid-1790s.

Cotton plain weave

Anne Lambert Clothing and Textiles Collection, Department of Human Ecology, University of Alberta

Purchased (2014.1.3abc)

Mount and photographs by Anne Bissonnette©

Figure 3

Hand-colored engraving on laid paper from Gallerie des Modes et Costumes Français, 2e Suite d'Habillemens de Femmes à la mode. Plate H.44: “Jeune Dame en Circassienne garnie de blonde, ornée d’un ruban tigré, coeffée d’un Chapeau galant avec un chignon lâche et tressé.”

Designed by: Claude-Louis Desrais (French, 1746–1816)

Engraved by: Etienne Claude Voysard (French, 1746–about 1812)

Publisher: Esnauts et Rapilly (French, 18th century)

Paris, France, 1778

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

The Elizabeth Day McCormick Collection

www.mfa.org

Link to the museum artifact

Several Material Culture graduate students from the University of Alberta have researched this ensemble for papers in the past few years and their research and conclusions have varied significantly. Like the other chintz garment presented in this exhibition, an investigation into its textile is a significant area of research that could uncover the original garment date. The cut and construction of the ensemble could be used to determine later periods when the garment was altered. As is typically the case for altered pieces, one looks for distinguishing stylistic features to understand the artifact as it currently stands.

The use of bust darts on the bandeau appears as the most innovative feature of this transitional ensemble, signaling the significant changes to dress behaviours in the 1790s. The bust darts create the delineation of individual breasts which signals a critical change in underpinnings away from traditional conical stays that compress and elevate the bosom. Though rare, surviving foundational garments from the 1790s exist. One example has gathered fabric "cups" over each breasts, while maintaining some traditional construction features, for example the use of waist tabs, which no longer sit at the natural waist in shorter transitional models. Old habits die hard! As early as 1793, the “Nouveau Dictionnaire français mentions the introduction of quilted and unboned “corsets,” instead of stays in a state of undress.”[1] 1795 is when shorter, lesser-boned transitional stays that separate and support individual breasts may have emerged in the United States.[2] Women may not have adopted this new aesthetic rapidly, but, when they did, other types of underpinnings, such as the shift, may have been modified with gussets at the chest to create a better fit (Figure 4).

Figure 4

White cotton shift with “Ulnette” monogram and gussets at the chest

Unknown creator and place of origin, mid 1790s to early to mid 1800s

Anne Lambert Clothing and Textiles Collection, Department of Human Ecology, University of Alberta

Donated by Titi Halle, Cora Ginsburg LLC (2019.9.42)

Mount, photographs, and montage by Anne Bissonnette©

When observing this ensemble, we can look at its construction and stylistic features to assess when it may have been last worn. If we hypothesize that it was worn draped in back, we need to corroborate this by searching for primary sources that depict this draped back on a narrow skirt, as well as an elevated waist, short sleeves and individual breast delineation. A 1796 fashion plate with a woman (left) identified as “Fig. 118” in Nicholas Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion fits the bill despite the fact that a round gown, rather than an open robe, is draped twice in back. Without the back drape, a much broader time span may be considered. Further research could search for surviving open robes with darted bandeaux or front panels, which are hard to identify in visual sources.

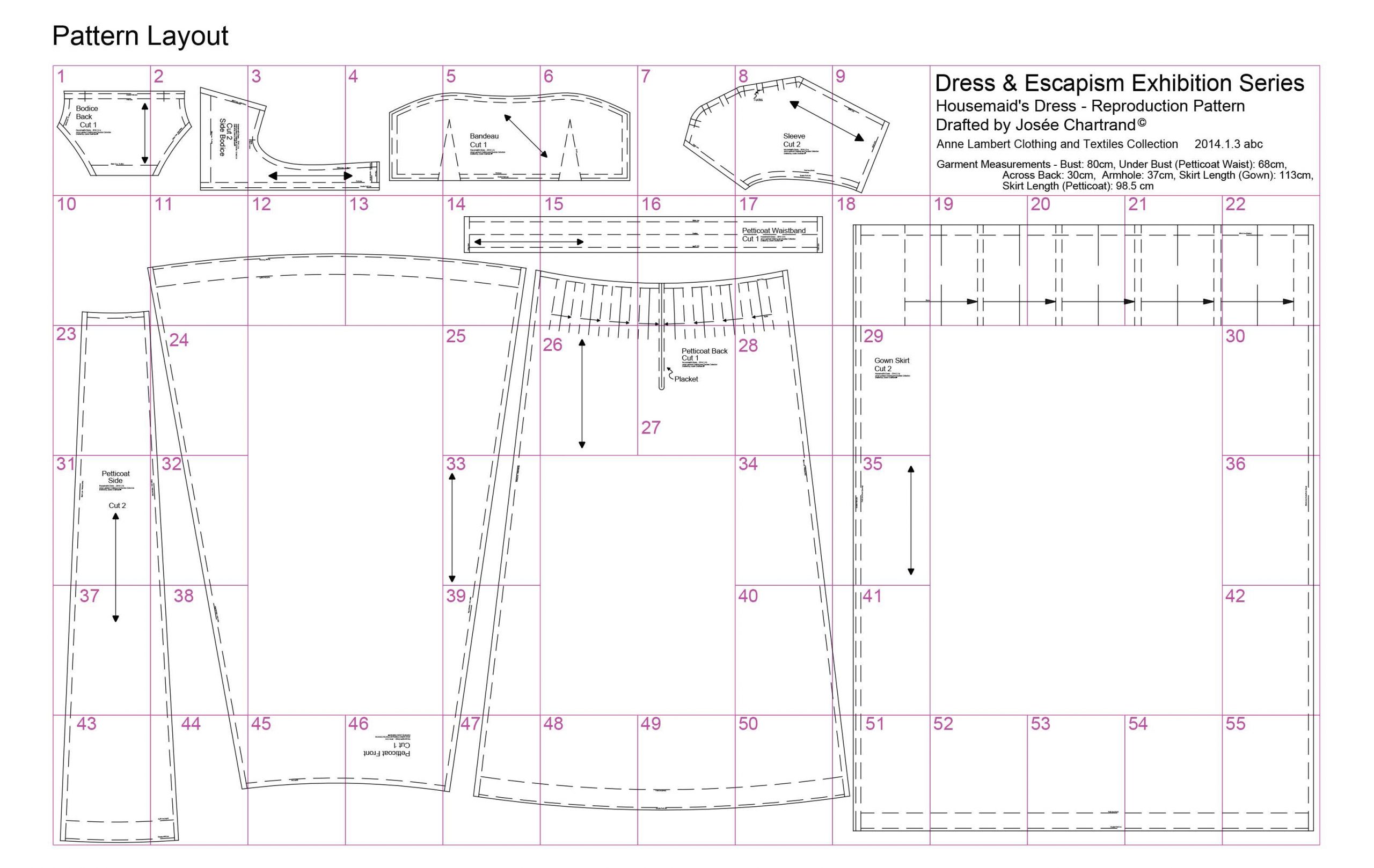

Creating a reproduction of a gown and wearing it to get an embodied experience is another way to do research. We invite you to give this a try by sharing a pattern of the gown through two PDF documents that can be printed in 8.5" by 11" format and assembled together (Figure 5).

In this endeavor and in most others, it is important to know that, when patterning a historical garment, one must decide the degree of accuracy that is required. The Housemaid’s Dress, like other 18th century gowns, is not entirely symmetrical. This is likely because the dress was made to measure for the body of the original wearer, and later modified to fit a new owner (the housemaid, in this case). The garment may also have been changed to suit new fashions. This may result in slight variations. When reconstructing any garment, one must decide whether to maintain these variations, or to even them out. If the goal is to re-create the piece exactly as it is, perhaps to exhibit a replica, then those differences are important to the integrity of the reproduction. However, if you are building the garment for another person, evening out the pattern for symmetry may be desirable to achieve the best fit for the wearer: no two bodies are alike, so it would be a disservice to incorporate minor asymmetries in the pattern that likely exist to suit another person's body. In the case of this exhibition research, our goal is to share the Housemaid dress pattern with individuals interested in creating this piece for themselves, at which point it is best to have a symmetrical pattern for ease of scaling. Our pattern has not been graded because we recognize bodies are not subject to even linear size progressions. Instead, we invite our followers to print this pattern, and true it to their own measurements. Not only will this result in a better fit, but we hope it will engage the maker with the original artifact through the making process.

This exhibition aimed to demonstrate the use of dress artifacts in scholarly research. It discusses the strengths and limitations of cut and construction investigations to help understand changing dress practices in the late eighteenth century. It draws on the expertise of numerous individuals who research eighteenth-century garments and learn through the making and wearing process. Immersed in another time period, their quests may go beyond mere entertainment.

Have you made reproductions of historical garments? What insights have you gained from the process?

Share your thoughts by e-mailing anne.bissonnette@ualberta.ca and we may add your story to bring different perspectives on this subject.

|

September 28, 2020 "I make reconstructions of medieval garments (also occasionally later eras) and I'm always impressed by how very efficient they are with fabric and other materials. I can make an entire kirtle using authentic techniques from about 3.3 yards of 45" wide fabric. Meanwhile the modern patterns I see for the same design use 4.5 or more yards to make a similar looking garment. The real version is made so that there is very little scraps even if you have to put in some extra labor or have some slightly wonky looking seams. The modern version prizes simplicity of construction and cutting pattern far above saving fabric. It makes sense when you think about how difficult it was to raise sheep, shear them, comb wool, spin it and then hand weave the fabric, but it wasn't something that I fully understood until I'd made both the modern Halloween costume version of a kirtle with modern techniques and the historical late medieval version. One of the other big differences I've found has been with ease of repair and reconstruction. When I wanted to repair a torn seam on my modern coat, I had to pull apart the entire lining and part of the waistband to get access to the pocket to mend it. Changing the size of a late medieval outfit after I gained weight was radically easier. I did not have to pull apart the outer fabric and underlining and could instead stitch through both of them at the same time. All of the exposed rough edges were places where I could easily adjust and repair. They might not look as elegant on the inside but there was a definite advantage. The last big difference I've noticed is about how body measurements are treated. Your average medieval seamstress was likely illiterate and could not do math. Therefore the methods we use for replicating medieval garments do not use numbers or writing but instead rely on pinning fabric draped onto the body of the person the garment is for. Most pattern making methods assume that the body is static; they assume that a 36" bust will remain a 36" bust. However when you pin fabric over a living body, this assumption goes out the window. The bust might be this big while I pin on one place, but if I adjust my pins, I can move flesh and make that measurement different. If I ask the person to sit down, that will also change the measurement and the fit. Which leads me to asking women to lay down flat on the ground during some parts of fitting because that will redistribute breast tissue upwards without gravity. Which in turn means that when my model stands up, the pinned garment will not let her breasts fall due to the fabric containing and shaping the body. In medieval tailoring body measurements are not static. The body and fabric move together and feed back on each other. It's a very different relationship with the body than simply making something for a 36" bust." Andrea Meier

|

[1] Anne Bissonnette, “Dessiné d'après nature: Renditions from Life in the Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1798‐9," Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 38, no. 2 (2015): 226, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1754-0208.12205.

[2] Saundra Ros Altman, Past Patterns #038: A Partially Boned Transition Stay Drafted from the Original at the Connecticut Historical Society, circa 1793-1820 (Dayton, OH: Past Patterns, 2009), 1. Cited in Anne Bissonnette, “Dessiné d'après nature: Renditions from Life in the Journal des Dames et des Modes, 1798‐9," Journal for Eighteenth‐Century Studies 38, no. 2 (2015): 237, https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/1754-0208.12205.

Support for the exhibition was provided by a KIAS Dialogue Grant from the Kule Institute for Advanced Study and a CIP Artist Project Grant by the Edmonton Arts Council and the City of Edmonton.

This exhibition draws on research supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council. The following individuals have contributed to Dr. Bissonnette’s research thus far: Josée Chartrand, Meg Furler, Peggy Isley, Katelin Karbonik, Patricia Siferd, and Sarah Woodyard.