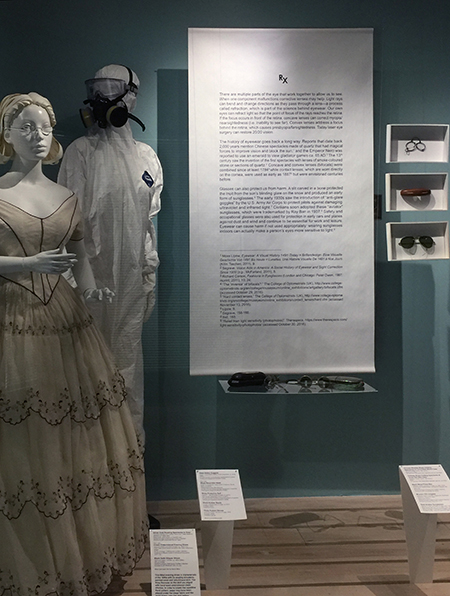

There are multiple parts of the eye that work together to allow us to see. When one component malfunctions corrective lenses may help. Light rays can bend and change directions as they pass through a lens—a process called refraction, which is part of the science behind eyewear. Our own eyes can refract light so that the point of focus of the rays reaches the retina. If the focus occurs in front of the retina, concave lenses can correct myopia/nearsightedness (i.e. inability to see far). Convex lenses address a focus behind the retina, which causes presbyopia/farsightedness. Today laser eye surgery can restore 20/20 vision.

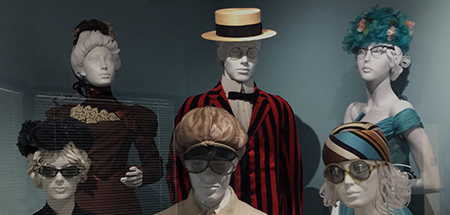

The history of eyewear goes back a long way. Reports that date back 2,000 years mention Chinese spectacles made of quartz that had magical forces to improve vision and block the sun,[2] and the Emperor Nero was reported to use an emerald to view gladiator games ca. 65 AD.[2] The 13th century saw the invention of the first “spectacles” with lenses of smoke-coloured stone or sections of quartz.[3] Concave and convex lenses (bifocals) were combined since at least 1784[4] while contact lenses, which are worn directly on the cornea, were used as early as 1887[5] but were envisioned centuries before.

Glasses can also protect us from harm. A slit carved in a bone protected the Inuit from the sun’s blinding glare on the snow and produced an early form of sunglasses.[6] The early 1930s saw the introduction of “anti-glare goggles” by the U.S. Army Air Corps to protect pilots against damaging ultraviolet and infrared light.[7] Civilians soon adopted these “aviator” sunglasses, which were trademarked by Ray Ban in 1937.[8] Safety and occupational glasses were also used for protection in early cars and planes against dust and wind and continue to be essential for work and leisure. Eyewear can cause harm if not used appropriately: wearing sunglasses indoors can actually make a person’s eyes more sensitive to light.[9]

[1] Moss Lipow, Eyewear: A Visual History 1491-Today = Brillendesign : Eine Visuelle Geschichte Von 1491 Bis Heute = Lunettes : Une Histoire Visuelle De 1491 à Nos Jours (Köln: Taschen, 2011), 9.

[2] Segrave, Vision Aids in America: A Social History of Eyewear and Sight Correction Since 1900 (n.p.: McFarland, 2011), 8.

[3] Richard Corson, Fashions in Eyeglasses (London and Chicago: Peter Owen, 1967; reprint, 2011), 19, 24.

[4] “The ‘inventor’ of bifocals?,” The College of Optometrists (UK), http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/college/museyeum/online_exhibitions/artgallery/bifocals.cfm(accessed Oct. 29, 2016).

[5] “Hard contact lenses,” The College of Optometrists (UK), http://www.college-optometrists.org/en/college/museyeum/online_exhibitions/contact_lenses/hard.cfm(accessed Nov. 13, 2016).

[6] Lipow, 9.

[7] Segrave, 158-160.

[8] Ibid, 160.

[9] “Relief from light sensitivity (photophobia)”, Theraspecs,https://www.theraspecs.com/photophobia-glasses-for-light-sensitivity-relief/ (accessed June 29, 2017).

Introduction | RX | Dose of Design | Fashion Aid | Artifacts in the Exhibition | Press Release |Story in The Quad |2017 Richard Martin Award

Photographs by Anne Bissonnette©

Cite this page (bibliography):

Bissonnette, Anne, Cybil Cameron, Katelin Karbonik, Naomi Milne, Katie Mooney, Danielle Peel, and Donnalee Riley. “Eyewear: Fashion with Vision, RX,” Exhibitions, Clothing and Textiles Collection, Department of Human Ecology, University of Alberta Museums, November 23, 2016. [INSERT URL].

LINKS TO ARTIFACTS BELOW MAY NOT BE RELATED TO THIS EXHIBITION