May 11, 2022 - March 1, 2023

Curators

Anne Bissonnette, PhD, Emma Carr, BA, Josée Chartrand, MA, and Qi Wang, BA

“A Riddle,

Wrapped in a Mystery,

Inside an Enigma”

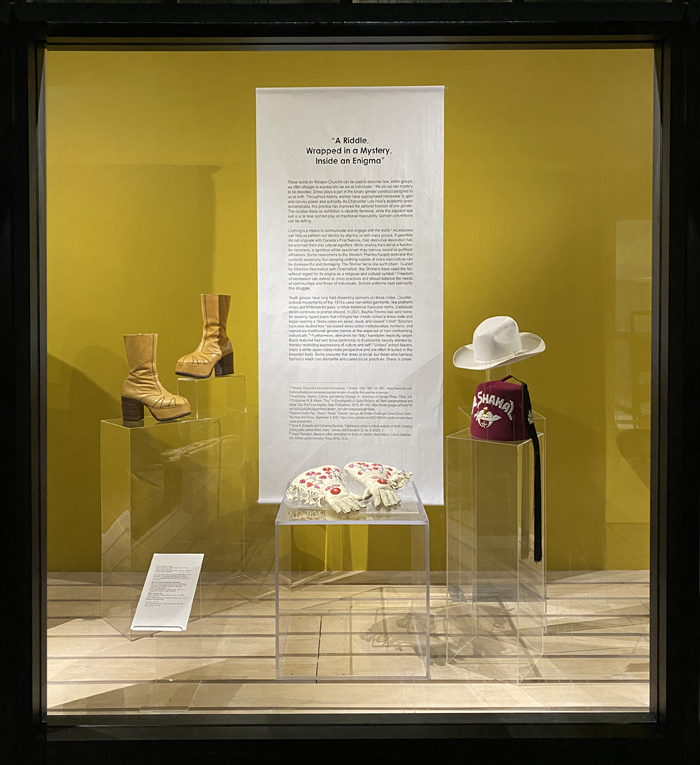

These words by Winston Churchill can be used to describe how, within groups, we often struggle to express who we are as individuals.[1] We are our own mystery to be decoded. Dress plays a part in the binary gender construct assigned to us at birth. Throughout history, women have appropriated menswear to gain and convey power and authority. As Chancellor Lois Hole's academic gown demonstrates, this practice has improved the sartorial freedom of one gender. The cocktail dress on exhibition is vibrantly feminine, while the adjacent teal suit is a far less spirited play on traditional masculinity.

Gender conventions can be stifling.

Clothing is a means to communicate and engage with the world.[2] Accessories can help us perform our identity by aligning us with many groups. If gauntlets did not originate with Canada’s First Nations, their distinctive decoration has transformed them into cultural signifiers. While cowboy hats serve a function for ranchers, a spotless white specimen may convey social or political affiliations. Some newcomers to the Western Prairies happily embrace this symbolic accessory, but usurping clothing outside of one’s own culture can be disrespectful and damaging. The Shriner fez is one such object.

Guided by Victorian fascination with Orientalism, the Shriners have used the fez without regard for its origins as a religious and cultural symbol.[3] Freedom of expression can extend to dress practices and should balance the needs of communities and those of individuals. School uniforms best exemplify this struggle.

Youth groups have long held dissenting opinions on dress codes. Countercultural movements of the 1970s used non-elitist garments, like platform shoes and embroidered jeans, to refute traditional masculine norms. Distressed denim continues to prompt discord. In 2021, Sophia Trevino was sent home for wearing ripped jeans that infringed her middle school’s dress code and began sporting a “dress codes are sexist, racist, and classist” t-shirt.[4] Scholars have also studied how “sex-based dress codes institutionalize, reinforce, and reproduce traditional gender norms at the expense of non-conforming individuals.”[5] Furthermore, demands for “tidy” hairstyles explicitly target Black textured hair and force conformity to Eurocentric beauty standards, thereby restricting expressions of culture and self. [6] “Unisex” school blazers imply a white upper-class male perspective and are often ill-suited to the breasted body. Some presume that dress is trivial, but those who harness fashion’s reach can dismantle antiquated social practices. Dress is power.

Anne Bissonnette, PhD

Emma Carr, BA

Josée Chartrand, MA

Qi Wang, BA

[1] “Winston Churchill's first wartime broadcast, 1 October 1939,” BBC 100, BBC, https://www.bbc.com/historyofthebbc/anniversaries/october/winston-churchills-first-wartime-broadcast.

[2] Fred Davis, Fashion, Culture, and Identity (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 3-6.

[3] Christopher M. B. Allison, "Fez," in Encyclopedia of Global Religion, ed. Mark Juergensmeyer and Wade Clark Roof (Los Angeles: Sage Publications, 2011), 401-402, https://books.google.ca/books?id=B105DQAAQBAJ&pg=PA402&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false.

[4] Isabella Grullón Paz, “‘Sexist,’ ‘Racist,’ ‘Classist’: Georgia 8th Grader Challenges School Dress Code,” The New York Times, September 4, 2021, https://www.nytimes.com/2021/09/04/us/politics/mask-dress-code-protest.html.

[5] Torrie K. Edwards and Catherine Marshall, “Undressing policy: a critical analysis of North Carolina (USA) public school dress codes,” Gender and Education 32, no. 6 (2020): 5.

[6] Cheryl Thompson, Beauty in a Box: Detangling the Roots of Canada's Black Beauty Culture (Waterloo, ON: Wilfred Laurier University Press, 2019), 23-24.