May 11, 2022 - March 1, 2023

Curators

Anne Bissonnette, PhD, Emma Carr, BA, Josée Chartrand, MA, and Qi Wang, BA

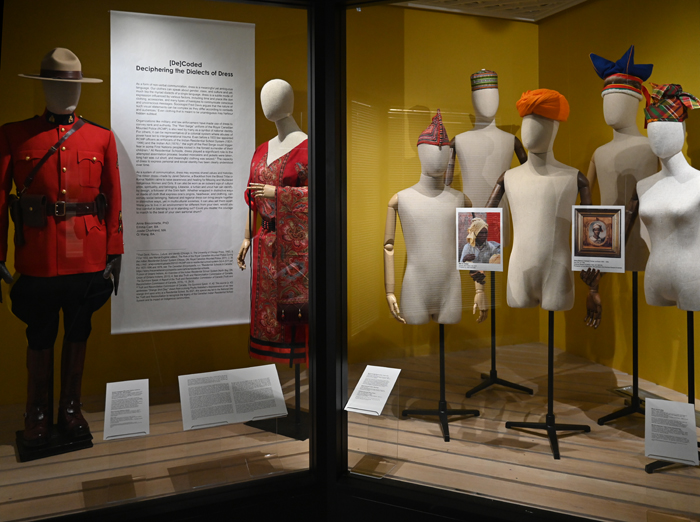

[De]Coded:

Deciphering the Dialects of Dress

As a form of non-verbal communication, dress is a meaningful yet ambiguous language. Our clothes can speak about gender, class, and culture and yet, much like the myriad dialects of a single language, dress is a subtle mode of expression influenced by various factors, including time and place. We don clothing, accessories, and many types of hairstyles to communicate conscious and unconscious messages. Sociologist Fred Davis argues that the nature of such visual statements can be complex as they differ according to contexts and audiences.[1] Even clothing that is meant to be unambiguous may harbour hidden subtext.

Organizations like military and law enforcement have made use of dress to convey rank and authority. The “Red Serge” uniform of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) is also read by many as a symbol of national identity. For others, it can be representative of a colonial system where abuses of power have led to intergenerational trauma. Even before a 1933 law appointed RCMP officers as enforcers of the Indian Residential School System (1831-1996) and the Indian Act (1876),[2] the sight of the Red Serge could trigger fear in some First Nations peoples rooted in the forced surrender of their children.[3] At Residential Schools, dress played a significant role in the attempted assimilation process: beaded moccasins and jackets were taken, long hair was cut short, and meaningful clothing was seized.[4] The capacity of dress to express personal and social identity has been clearly understood over time.

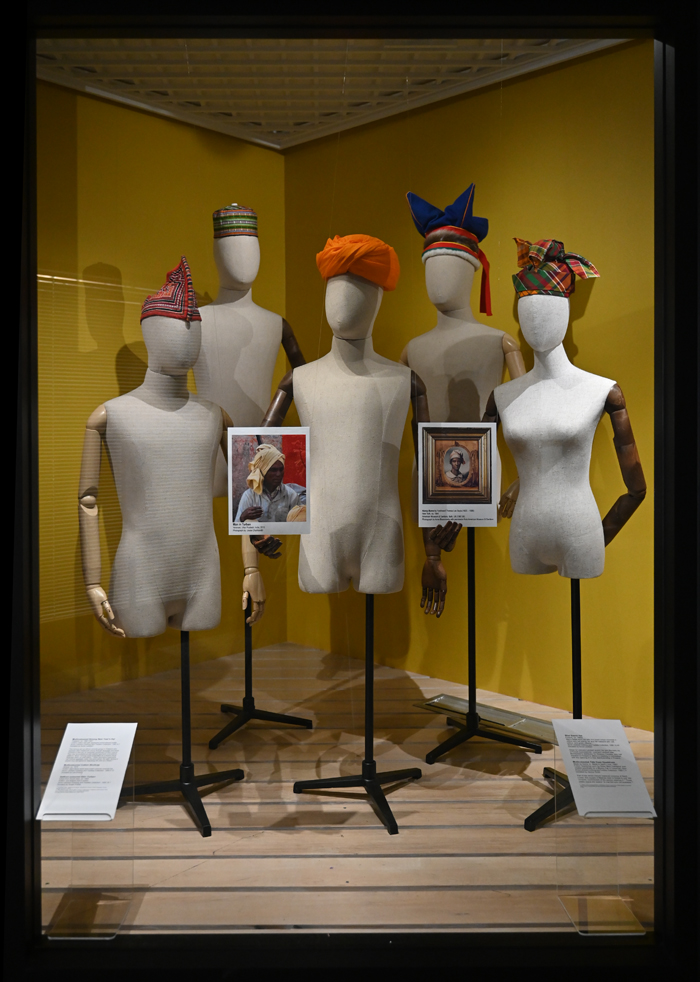

As a system of communication, dress may express shared values and histories. The ribbon dress—made by Janet Delorme, a Blackfoot from the Blood Tribe or Kainai Nation—aims to raise awareness and healing for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls. It can also be worn as an outward sign of cultural pride, spirituality, and belonging. Likewise, a turban and uncut hair can identify, by design, a follower of the Sikh faith. Whether wrapped in distinctive ways or made of cloth that express one’s origins, headwear, and clothing, can convey social belonging. National and regional dress can bring people together in distinctive ways, yet in multicultural societies, it can also set them apart. Were you to live in an environment far different from your own, would you find comfort in blending in or in standing out? Could you muster the courage to march to the beat of your own sartorial drum?

Anne Bissonnette, PhD

Emma Carr, BA

Josée Chartrand, MA

Qi Wang, BA

[1] Fred Davis, Fashion, Culture, and Identity (Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press, 1992), 8.

[2] For 1933, see Marcel-Eugène LeBeuf, The Role of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police During the Indian Residential School System (Ottawa, ON: Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 2011), 2, 39, https://nctr.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/RCMP-role-in-residential-school-system-Oct-4-2011.pdf. For 1831-1996 and 1876, see The Canadian Encyclopedia, s.v. “Residential Schools in Canada,” https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/residential-schools.

[3] Union of Ontario Indians, An Overview of the Indian Residential School System (North Bay, ON: Union of Ontario Indians, 2013), 4. See also Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak: A Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2015), 15, 28-30.

[4] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Survivors Speak, VI, 42. This source (p. 42) addresses “Orange Shirt Day,” drawn from a young Phyllis Webstad’s dispossession of her new orange shirt upon entry at a Residential School. By 2021, this special day led to the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation to recognize the legacy of the Canadian Indian Residential School System and its impact on Indigenous communities.